Circular building

Recycling with aesthetics

by Joachim Goetz

With the establishment of the circular economy, construction should make its contribution to the EU’s climate goals. And not lose sight of aesthetics in the process.

Reused materials in architecture? According to a widespread cliché, you only build a house once in your life — if at all. Should we be content with second-hand materials?

In any case, the examples realized by avant-gardists (of architecture) do not look like scraped-off suits from the flea market. Most of the buildings — so far few in number — do not even show that the (second) materials used have been given a new lease of life, so to speak. This applies to the buildings realized by the Rotterdam-based Superuse Studio as well as to the Landshut “Schatztruhe” (treasure chest) totally renovated by the Munich-based architects Stenger2, the recycling house by Cityförster in Hanover or the Hamburg “Moringa” by kadawittfeldarchitektur, which is still in the process of being built.

Architects have taken up the challenge, as lighthouse projects and initiatives illustrate. But there are still many reservations, prejudices and problems in implementing this almost revolutionary redefinition of building.

A consumer society in which a new shirt often costs less than washing and ironing it is initially overwhelmed by such unconventional ideas. Even among down-to-earth craftsmen and established architects, the idea of reuse did not trigger any stormy enthusiasm for a long time. Not to mention the building industry, which would then have to realign itself or, in the worst case, would have nothing left to do.

Building authorities, regulations and laws are also not yet properly prepared for a “circular economy” in the construction industry.

Recycling leftovers is something deeply traditional, something widespread and by no means disreputable. Just think of the cuisine, where pizza, paella and stew are extremely popular dishes that were originally invented as a way of using leftovers after a sumptuous feast. The patchwork technique also has a long tradition, for example with the quilts of the Amish, the ancient Japanese techniques Ranru and Boro or the patchwork carpet from our culture.

Leftover recycling at the construction site?

Now, one has to admit that buildings generally last longer than clothes or the remnants of a festival. Moreover, it is not only among the monuments that there are examples that have hundreds of years under their belt and have been repeatedly adapted to new functions and uses. Moreover, in early times, even in building, there existed an admittedly not particularly imitable secondary use of (precious) building materials. The Egyptian tomb pyramids were partly demolished in order to build simple houses. The same happened with knights’ castles, whose ruinous condition was not first caused by wind and weather — but by resourceful minds that preferred to build their medieval homes with old stones rather than with new crooked timbers.

Incidentally, the use of so-called spolia has also been popular among architects for centuries. These are usually building elements from earlier times and styles. A good example is the Bavarian National Museum in Munich. Here, the historian Gabriel von Seidl skillfully mixed styles and eras. Thus, carved portals, wrought-iron grilles, ceilings, murals and much more have been installed there for the second time.

The rooms were designed specifically for the use of such elements. They were supplemented with invented and imitated architectural details. The result is a museum building with a very special, very unusual flair that may seem strange to some.

In accordance with Robert Venturi’s classic “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture”, the result was not a genius architect’s design, but something baked together, a potpourri of styles. The most famous example of this is surely St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice.

Away from demolition and new construction

Now something is changing — at least in words, demands, manifestos or the EU initiative of the New European Bauhaus. Why? The construction industry is falling into disrepute as a climate killer. Through the production and transport of building materials and the operation of buildings, it is responsible for 60% of material consumption, 50% of mass waste generation, around 40% of CO2 emissions and 20% of plastic consumption worldwide.

The current practice of demolition and new construction generates untold amounts of useless construction waste, as it often consists of composite and mixed materials that can no longer be separated. The special sand suitable for making concrete is becoming scarce and expensive. Incidentally, desert sand that has been ground round by wind and weather is no good for this purpose. And it is probably only a matter of time before the increasingly popular renewable building material wood (link) also becomes a scarce commodity.

Here, too, it is worth taking a look at history: In Roman times, the forests of Italy were cut down to build war fleets. The regrowth was mainly the macchia, the thorn bush scrub. It would not be positive if something similar were to happen again in the Amazon rainforest and in the forests of our latitudes.

How more recycling can succeed is shown not only by innovative projects and university courses, but also by remarkable initiatives dealing with “urban mining” and “harvesting.

Re-use materials

In Munich, the “initiative zirkulæres bauen” is planning a pilot project for circular building in Metzgerstrasse together with Kooperative Großstadt e.G.. The initiative, which acts as a component hunter and specialist for component reuse, is also setting up a network between politicians, planners, builders and companies.

The Viennese “materialnomads” have established themselves as pioneers of processes for the circular economy in Austria. They explore the material and cultural value of vacant buildings that are to be demolished due to safety regulations, economic or political decisions. Since its founding in 2017, the Viennese have already picked up more than 60,000 building components and made them available for reuse.

Natural raw materials such as wood, glass, metal and stone are particularly suitable. In the case of the new building project magdas Social Business, a subsidiary of Caritas of the Archdiocese of Vienna, mainly materials “harvested” in the vicinity of the city were used. Among the 13.6 tons of re-use material were, for example, oak strip flooring, mobile partition wall elements, aluminum perforated sheet elements, natural stone panels, box doors, mailboxes, handrails made of oak, steel panels and larch wood, door frames and door leaves as well as pendant lights. A total of 17.258 metric tons of CO2 equivalents were saved, thanks in part to the short transportation distances. This could heat a single-family house for over five years.

Demolition architecture

The German impact startup Concular, which describes itself as a “market leader for the reintroduction of materials,” works in a similar way. Circular construction is made easier with the help of intelligent data-based mediation. Components of a state library in Augsburg, for example, or the Siemens conference center in Feldafing, which is to be replaced by a new solid wood building, have been and are being offered.

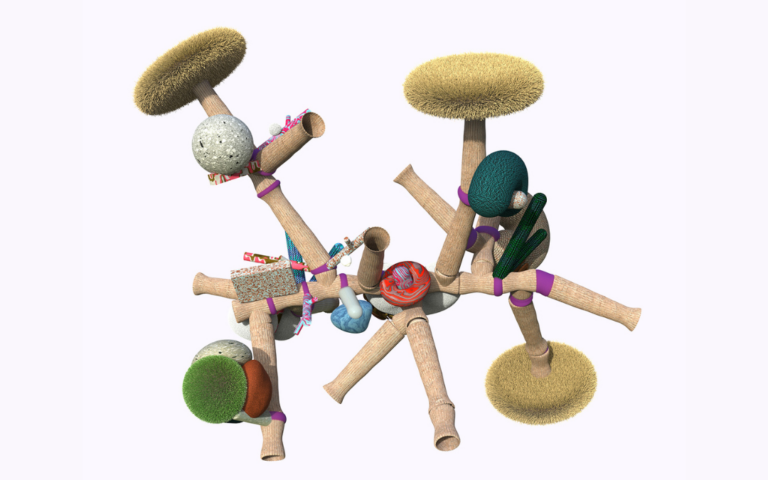

Of course, mineral building materials — natural stone, bricks, concrete, etc. — are particularly interesting for construction. — are of particular interest. A lot of so-called gray energy is stored in these materials. A workshop held by the Institute of Architectural Technology at the Graz University of Technology investigated the potential of building material recycling in a demolished building under the title “city remixed”. As a result, the deconstruction of buildings must be carried out in a similarly planned and detailed manner as the new construction or erection. In order to recover raw materials, an “architecture of demolition” is required.

Built examples

In Landshut, Stenger2 Architekten overhauled a 500-year-old log house in Pfettrachgasse. They used beams and boards from a Landshut townhouse whose roof truss had been dismantled. Only what was no longer structurally sound was replaced.

The great age of the building, which was once built in a CO2-neutral manner using regional building materials, commanded the respect of the architects and owners. They wanted to allow this house, which had been home to a variety of different uses for half a millennium, to live on in the form of “endless use.”

This means that future users should also be able to repair the house. Thus, cement, plastics, plaster, dispersion and bituminous building materials were largely avoided. Instead, almost forgotten materials such as swamp lime, clay bricks, clay, wood, reed, hemp and linseed oil celebrated a joyful revival.

The author Joachim Goetz studied architecture in Munich and Denver/Colorado with subjects such as art and building history, sculpture, photography, watercolor, landscape and product design. He worked in architectural offices including GMP, won competitions with Josef Götz and built a house with Thomas Rössel and Heinz Franke. He has been a full-time writer since 1990, and was an editor at Baumeister and WohnDesign. Publications were made in national and international daily, public, art and design magazines such as SZ, Madame, AIT, Münchner Feuilleton, AZ or Design Report. Interviews were conducted — for example with Ettore Sottsass, Günter Behnisch, Alessandro Mendini, Zaha Hadid, James Dyson, Jenny Holzer, Walter Niedermayr or Daniel Libeskind. He has also worked for companies such as Siedle, Phoenix Design and Hyve. For Sedus he was co-responsible for the first digital architecture magazine a‑matter.com (1999–2004) as well as the competence magazine “Place2.5” (2011–2014). For bayern design and the MCBW he is repeatedly active as an author. His work was awarded a media prize for architecture and urban planning by the German Federal Chamber of Architects. J. Goetz is also a dedicated consultant to smaller companies on special design, marketing and offbeat issues.