by Sarah Dorkenwald

A special kind of vacuum cleaner was already on display during mcbw start up a few years ago. It stood out not only because of its unique aesthetics with a housing made of cork, but also because of its functionality, which consisted primarily of extending its service life. The vacuum cleaner was designed by Franz Junghans and Christof Mühe, then product design students at the Bauhaus University in Weimar. Instead of a complete housing, the vacuum cleaner is made up of individual elements that can be easily replaced or repaired. Instructions on the Internet are intended to help people do this independently and without incurring large service costs.

The entire life cycle counts

When it comes to a vacuum cleaner or other commercially available electrical appliance, most people associate sustainability with energy efficiency, meaning lower power consumption during use compared to other appliances or previous models. However, if one wants to equate energy-efficient with sustainable, the product should fulfill other factors. These include, among other things, service life as well as the energy used in manufacturing. This in turn includes other aspects that should be considered from the outset during product development: Can the product be repaired? What materials are used and are they recycled or recyclable? What happens after the end of use?

Materiality plays a central role in the energy balance and involves weighing renewable or finite raw materials. But transportation also consumes energy, and is not only used to transport consumer goods from A to B. The production of raw materials and individual production steps are also often distributed around the globe. A laptop, for example, consumes between one-third and one-half of the energy it needs during its entire life cycle of several years, from production and use to disposal. The useful life of this device should be correspondingly long. (Source: https://www.ecodesignkit.de).

The entire product cycle must be considered.

Strictly speaking, we can also only speak of an electric car as energy-efficient or climate-friendly if the entire product cycle is taken into account, i.e. not only the electricity for driving, but also the energy for the production of electricity and the car, as well as the disposal of the vehicle. In addition, due to the energy-intensive battery production process, an e‑car initially generates higher emissions compared to a car with an internal combustion engine. The latter requires an average of five to seven metric tons of greenhouse gases in production, while the figure for electric cars is ten to twelve metric tons. (Source: https://www.verivox.de/).

So there is still a long but indispensable road to climate-friendly e‑mobility — and an even longer one to climate neutrality.

Transformation through design

Technical innovations alone are not enough to meet the requirements of environmentally friendly alternatives. Companies are faced with the challenge of taking into account both economic and social issues along the value chain and of questioning and rethinking existing systems from the ground up.

Especially methods, tools and models of thinking that come from design help to accompany these transformative processes in a multi-perspective and transdisciplinary way in order to stimulate future-oriented forms of production and new developments.

The fact that it is not so easy to design better products was illustrated in 2019 by the exhibition “Circolution,” developed by master’s students of industrial design and architecture at the Technical University of Munich. They addressed the question of why we still attach such little value to things, materials and recyclables that they end up in the trash rather than being reused in material cycles.

They wanted to show how complex the question of the right material is by means of simple comparisons, such as a cloth bag and a paper bag. While the production of the paper bag is usually worthwhile after at least three uses, the fabric bag, on the other hand, must be used at least 130 times if the impact on the water or the acidification of the soil is also included in the life cycle assessment.

The design work ‘Bottom Ash Observatory’ by Dutch designer Christien Meindertsma also shows us in a visually captivating and impressive way how wasteful we are with our environment. Meindertsma examined the slag from 100 kilograms of incinerated household waste. From 25 kilograms of bottom ash, the waste of waste, the designer extracted a wealth of valuable materials such as zinc, aluminum and silver. Transposed as an encyclopedic book, it illustrates the amazing wealth that this slag reveals.

The future is circular

What if we could find a way to design products, services and business models in such a way that they would benefit us humans as well as the environment and the economy? That’s the question posed by IDEO, an international design and innovation consultancy. It focuses on the Circular Economy as a radical promise, replacing traditional principles of industrial production and its throwaway economy, in favor of the Circular Economy model.

Together with the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, they are committed to helping entrepreneurs and designers use the circular design guide to design circular processes that keep data, nutrients and materials flowing and transform their business model into one that is economically, socially and environmentally successful. Instead of a linear economy where materials remain unused after a product’s demise, and as waste cause us humans and the environment major problems, these “take-make-waste” elements should be transformed into circular processes.

Only when waste is avoided and resources circulate can nature regenerate, biodiversity loss be mitigated, and social needs be brought into focus.

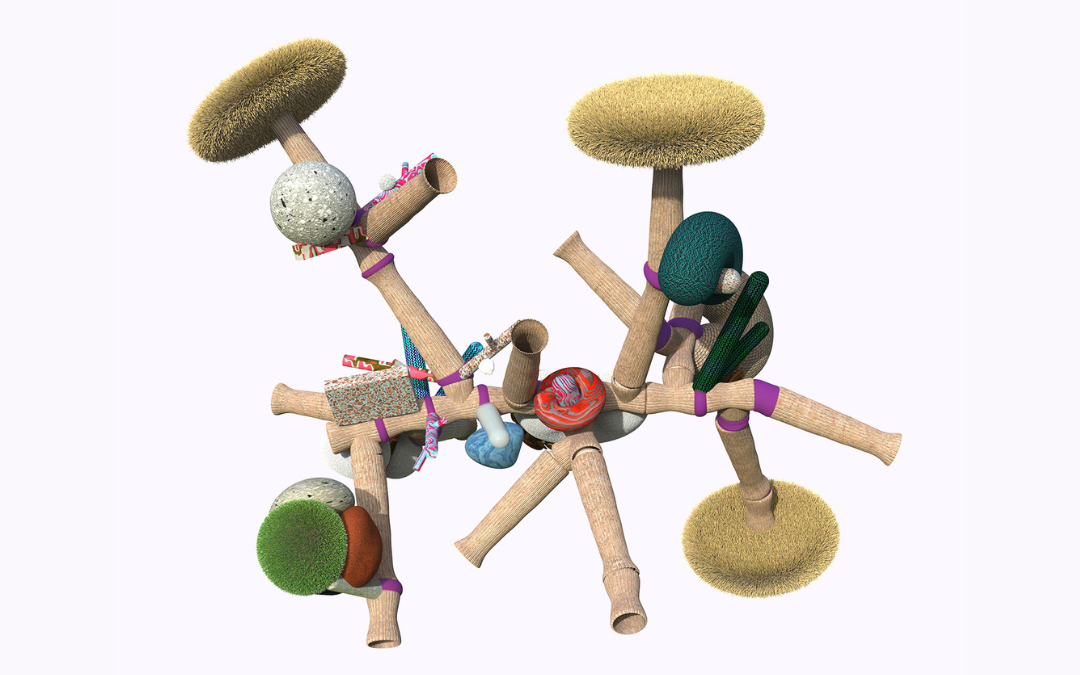

The BMW Group is setting a good example here and invited star designer Patricia Urquiola to make Circular Design a playful experience within the Group. As part of the new communication and experience platform “RE:BMW Circular Lab”, four exciting characters representing this new approach were developed under her direction with a great deal of creativity and experimentation to create a deeper awareness of sustainable action and circular thinking.

What is needed, then, is a different corporate culture that has the courage to open itself up to the new and the unknown.

So what is needed is a different corporate culture that has the courage to open itself up to new and unknown things.

Steelcase, with its Learning and Innovation Center in Munich, is also looking at new circular forms of production. In cooperation with BASF, in the future harmful or even toxic residues produced during computer production will no longer be incinerated during disposal, releasing vast quantities of pollutants into the atmosphere, but will be used to manufacture a new, fully recyclable stool.

And the big players are following suit: In ten years at the latest, Ikea wants to design all its products according to circular economy principles and produce them exclusively from recycled or renewable materials.

An arduous path, but if we are honest with ourselves, this path is not an alternative to existing systems, it has no alternative! In this sense: Let’s rethink the system by design!

The graduate (Univ) designer Sarah Dorkenwald practices a critical approach to design in her creative and theoretical work. In exchange with other disciplines she questions common approaches and social conventions and wants to show alternatives in dealing with resources, production and distribution as well as living together with current positions in design. She is a professor at the University of Communication and Design in Ulm. Together with design theorist Karianne Fogelberg, Sarah Dorkenwald founded the Munich-based studio UnDesignUnit. They combine skills and methods from design and design theory and work at the interface with other disciplines and forms of knowledge. Sarah Dorkenwald writes regularly for design journals as well as trade publications.